In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Benjamin, 1936), Benjamin argues that mechanical reproduction of art reduces and devalues its aura, and that as this happens, art becomes based on political theory rather than relying on the context of the art itself. Benjamin focuses on the impact of technological advancements leading up to the 1930s, and specifically the ability to mechanically reproduce works of art in the form of film and photography, arguing that the traditional aura of an artwork — its unique presence and authenticity, and its physical and cultural locale — diminishes with each reproduction: that reproducibility detaches the work of art from its ritualistic and traditional origin, and becomes a mass-produced commodity (Benjamin, 1936). In Benjamin’s own words, “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its prescience in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” (Benjamin, 1936.) The dissemination of mechanically-reproduced art has profound political and social implications, Benjamin argues, as it loses its elitist character when it becomes accessible to all. This also shifts the way people perceive and experience art — reproductions can be seen in any environment, and taken out of its original context, which can alter the perceiver’s perception of it. Benjamin also discusses the implications of these changes vis-à-vis traditional art forms, and argues that film and photography could have the potential to revolutionise not only the production, but also the perception of art. Historically, this holds true: during the Crimean War in the 1850s, war photography from the likes of Roger Fenton was born (Woodis, n.d.), allowing, for the first time, the general public to see the horrors of war — although much of this photography was staged, requiring long exposure times. Nevertheless, this eventually evolved into a means of swaying the public, especially by the 1930s, in the lead-up to the Second World War, the most politically-charged time in Germany since 1918. Being Jewish, and writing during the height of antisemitism in Europe, Benjamin must have felt this more than most. He references both Bertolt Brecht and Franz Kafka who, like Benjamin, were both German-Jewish writers (Arendt, 1968) (Bronner, 2008) (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1998) living in Germany through the same times. While Benjamin agreed with Brecht’s anti-capitalist and near-Marxist ideologies (Davidson, 2009) (Squires, 2021) (Bentley, 1998), Kafka saw the evils of bureaucracy as being a fight of the ‘elites’ versus the ‘expendables’, rather than of left-versus-right (Berkoff, 1988). Somewhat ironically, Brecht’s art was the stage, and theatre was undoubtably the first deliberately-reproducible form of art; the difference from traditional art being that each performance is unique, even if the same script is used — giving way to Benjamin’s argument that exact-reproductions are what diminish the aura of art, leading on to his next argument that, while the original aura may be lost, the reproductions give it a new aura: the ability to reproduce and distribute art widely gives it new significance, and has the possibility of creating a new cultural impact, in a similar way to how Brechtian theatre uses verfrumdungseffekt to make audiences question their own internal politics and morality (Bentley, 1998) (Brecht, 1948), and how Kafka literarily explores the Sisyphean cycle of lives controlled by the bureaucracy of politics — the Kafkaesque Nightmare (Benjamin, 1934). Benjamin goes on to reflect on the loss of authenticity of experiencing art due to mass mechanical reproduction, and the role of the viewer within this paradigm, no longer being as passive, as art becomes a call-to-action, requiring the viewer to actively engage with and make their own interpretations of an artwork, based on its new context and environment. Benjamin raises questions about the transformative effects of technology on art, the democratisation of culture and the changing nature of artistic experience in an age of mechanical and technological reproduction.

L’art pour l’art is a term Benjamin discusses towards the end of his essay, first attributed to the philosopher Victor Cousin in the latter half of the 19th Century (Schaffer, 1928), expressing the idea that ‘true’ art is is utterly independent of social, political, didactic, and moral functions (Wilcox, 1953), needing no justification and being autotelic (Baldwin, 1901), or complete in and of itself. This, however goes too far the other way. ‘True’ art shouldn’t have to be meaningless beauty — although it can be — but to say this is the only ‘true’ form of art is absurd. Ever since cavemen drew on walls, art has had meaning, elicited emotion, or called for action — but art just for the sake of art, equally, would not stand up to scrutiny out of the context of being an elitist power-grab, as autotelic art would. This raises a question: what actually is art? “Art for art’s sake” could easily be attributed to such modern works as Maurizio Cattelan’s $120,000 piece ‘Comedian’, which is simply a banana duct-taped to a wall (Hudson, 2019).

The banana was taken off the wall and eaten, and then simply replaced with a new banana, which in turn was promptly removed after “several uncontrollable crowd movements” (Hudson, 2019).

This is, surely, art for art’s sake. If it weren’t revered and labelled as ‘art’, no one would care, and it would not have received the global attention it did. If someone broke into a display at The Louvre and ate the Mona Lisa, it could not be replaced from a pack of six from Sainsbury’s. This also links to Benjamin’s ideas of elitism within art, as, if this was done by someone unknown, it is not very likely that it would have received any attention at all, whereas a beautiful piece of artwork will always be widely-considered beautiful, even if it takes years to become known — many artists’ work was not known about nor considered ‘good’ until after their deaths, some forgotten masterpiece found in an attic — but it is fairly safe to say that a banana found taped to the wall of a deadman’s home would simply have him rendered not of sound mind. It is the intrinsic beauty of art that is appealing to the vast majority of people which gives it value; l’art pour l’art is simply an elitist ploy to gate-keep the ability to create art for the sake of it, only giving money and attributing social allure to those works made by people already of high status, either through reasons of tax evasion (Horvath, 2020) or elitism (Bergson, 1983), thus, keeping the ability to produce art that is autotelic away from the masses, disallowing them the opportunity to create movements and spark conversations. However, and with some sense of irony, the reproducibility of l’art pour l’art is sometimes more difficult — finding or somehow creating an identical banana would be the only way to create an exact copy of ‘Comedian’. Of course, in reality, anyone with no artistic background whatsoever could tape a banana to a wall: the bit that’s difficult to reproduce is the art of being the already-famous, already-rich artist, supported by the entire elite art community.

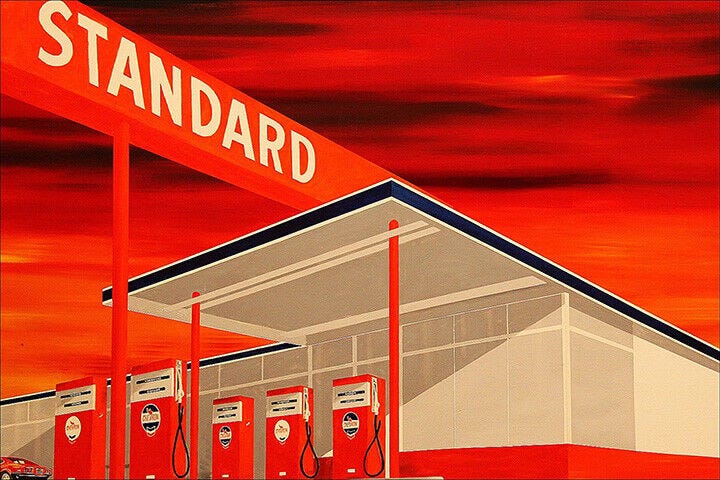

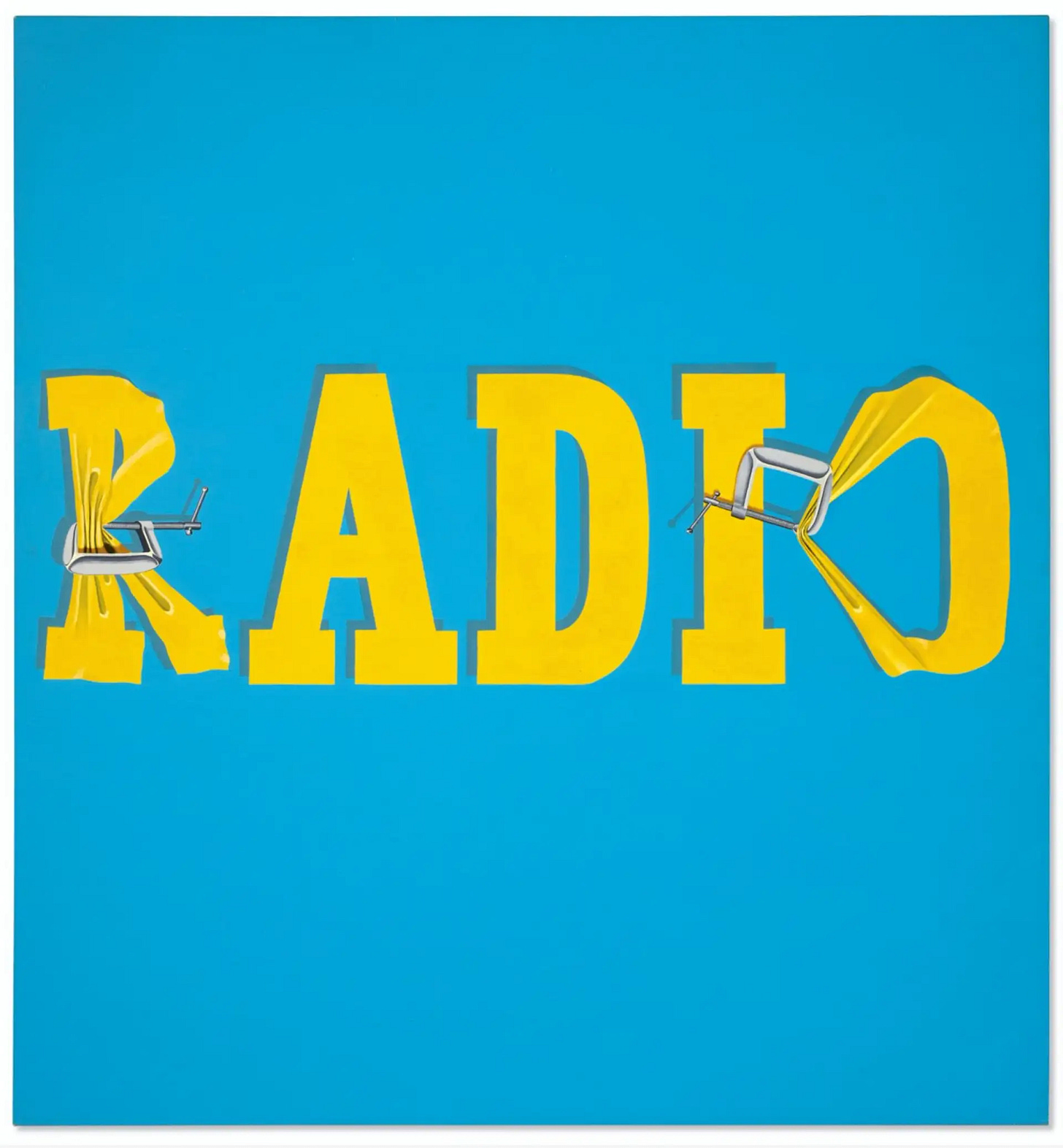

With digital reproduction, you can create infinite copies, as close to exact as is possible, with the press of a button. But is this really a bad thing? Benjamin’s claim that this devalues it, razes its aura, raises the question of elitism all over . Benjamin claims this to be a negative, but surely, mechanical — and now digital — reproduction of art only allows it to be seen by more people, allowing its message to be spread further afield. Yes, it may take it out of its original context, but this is no different than taking an artwork from Ruscha’s studio and putting it into LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Digital reproduction, if anything, makes it less elitist than putting it in a room you have to pay to enter. In 2024, a ticket to The Louvre will cost €22 (Demos, 2023) — this isn’t massive, but it is €22 more expensive than it would be to type “Da Vinci Art” into a search engine. The experience is entirely different, undoubtably, but it does mean that digital reproduction allows the everyman to see almost any piece of art, for the first time ever. This being said, Benjamin died in 1940, so he never experienced digital reproduction: had he, perhaps his thoughts would have changed. Notwithstanding this, although there is a plethora of positive repercussions attributed to digital reproduction, it does lose its aura in the most technical sense — it is no longer unique; no longer is there only one way to view art, in one setting, in one context. However it is not accurate to say that art can ever be completely reproduced: the original is still the original, and even though searching “Da Vinci Art” is twenty-two euros cheaper than visiting The Louvre, people still go, because there is something intrinsically unique about the original of anything. In 2019, Ed Ruscha’s 1964 piece “Hurting the World Radio No 2” sold for almost forty-one million pounds (Fraser, n.d.), even though a high-quality scan is available online, which could be printed for less than it would cost to visit The Louvre.

Even though copies are available, people will always have a connection to the original. This concept was perhaps best shown in the 2006 study of 38 children between three and six years old, where they were given the option between a personal artefact that was their own, or an identical, ‘cloned’ copy (really, they were given the same item regardless), showing clearly that they favoured the original (Hood, Bloom, 2007). The study’s abstract explores tangible ‘aura’:

‘Children prefer certain individuals over perfect duplicates,’ Bristol Cognitive Development Centre & Department of Experimental Psychology and Yale Department of Psychology, 2006.

Adults value certain unique individuals—such as artwork, sentimental possessions, and memorabilia—more than perfect duplicates. Here we explore the origins of this bias in young children, by using a conjurer’s illusion where we appear to produce identical copies of real- world objects. In Study 1, young children were less likely to accept an identical replacement for an attachment object than for a favorite toy, […] suggest[ing] that young children develop attachments to individuals that are independent of any perceptible properties that the individuals possess.

This is particularly interesting, as it shows people have an innate connection to what they consider to be an ‘original’. It becomes obvious that the value of an artwork comes not from its aura, but from its originality; at least, with traditional, autotelic art. In recent years, Artifical Intelligence has become a great conversation topic, and its generation of art has sparked much debate — yet, somehow, AI art tends to hold much less value than man-made art. Aside from the great controversy when some modern artists saw parts of their own works suddenly reproduced and adapted, with no permission seeded, credit given, or copyright accruable, AI lacks creativity, ingenuity or the rewards of the artistic process. The element of ‘randomness’ and this lack of artistic creativity means that people always unfalteringly prefer human art over that made by AI (Dolan, 2023). If AI (or randomly-typing monkeys) were to generate a new Shakespeare play or predict a lost work (Idao, 2021), it would hold less value, as people inherently prefer genuine human creations, as the Yale-BCDC study shows. The existing value of Shakespeare's plays stems from their origin in the human mind: the human race is an infinite selection on monkeys, speaking out infinite strings of words eternally, and one of us already wrote Hamlet.

The loss of the aura of art is almost a non-issue: Benjamin’s essay is extremely interesting and effective in exposing the downsides of mechanical reproduction, taking the original context away, but in the age of digital reproduction, it is also impossible to find art that isn’t surrounded by context anyway — and, regardless, any message contained within art (one’s mind immediately goes to the most modern-day political artworks, by the likes of the Guerrilla Girls) are still seen, still appreciated and still heeded, perhaps even on a greater scale than would otherwise be. Brecht put his political messages into theatre for the sole reason of its reproducibility, to spread his message as wide as possible. Performances that weren’t directed by Brecht himself didn’t lose anything, as it was still his work, despite the potential ‘loss of aura’. When Kafka died, his last wish was for his manuscripts, letters and journals to be burned (Batuman, 2010). If this request had been followed, there would never have been the political movement he sparked, a cry for change from the endless bureaucracy of municipal labour and governmental control. The conversations and both artistic and political movements sparked by Kafka were a direct result of mechanical, and then digital, reproduction, without which, there would be no concept of Kafkaism, and no real way to describe the Kafkaesque nightmare. Digital reproduction, especially using Benjamin’s ideas about photography and film, take this even further, allowing art to be seen by all, transcending the restrictions of elitism, geography, status or language. Art is no longer a bourgeois commodity to be enjoyed by the precious few; it is a vehicle for change, an expression of beauty, and an exhibit of uniqueness — allowed and enabled by digital reproduction.

Bibliography

Arendt, H. (1968). Walter Benjamin, The New Yorker, October 19, 1968, p. 65.

Baldwin, J. (1901). Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, New York, The Macmillan company; London, Macmillan & co. ltd.

Batuman, E. (2010), Kafka’s Last Trial, New York Times, 22 Sep 2010 [online]. Last accessed 2 Jan 2024: https:// www.nytimes.com/2010/09/26/magazine/26kafka-t.html

Benjamin, W. (1929) Picturing Proust, Underwood, J. A. (tran.), London: Penguin Random House.

Benjamin, W. (1934) Franz Kafka, Underwood, J. A. (tran.), London: Penguin Random House.

Benjamin, W. (1936) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Underwood, J. A. (tran.), London: Penguin Random House.

Bentley, E. (1959, 1983) The Caucasian Chalk Circle: Preface, London Penguin Classics, 2007.

Bentley, E. (1998), Bentley on Brecht, Michigan, Applause Books.

Bentley, E. (1999) The Caucasian Chalk Circle: Prologue, London, Penguin Classics, 2007.

Berkoff, S. (1988), The Trial, Metamorphosis, The Penal Colony: Three Theatre Adaptations from Franz Kafka, Oxfordshire, Amber Lane Press Ltd.

Bersson, R. (1983), For Cultural Democracy: A Critique of Elitism in Art Education, Journal of Social Theory in Art Education, Vol. III, 1983, James Madison University [online]. Last accessed 29 Dec 2023: https:// scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jstae/

Brecht, B. (1948), Parables for the Theatre: Two Plays by Bertolt Brecht, University of Minneapolis Press, 1948; Penguin Classics, 2007.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (1998, last updated 2023). "Bertolt Brecht". Encyclopedia Britannica [online]. Last accessed 6 Jan 2024: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bertolt-Brecht.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (2013), Art for Art’s Sake. Encyclopaedia Britannica [online]. Last accessed Jan 4th 2024: https://www.britannica.com/topic/art-for-arts-sake.

Bronner, E. (2008). How Jewish was Franz Kafka? The New York Times, Aug 18 2008 [online]. Last accessed Jan 6th 2024: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/18/world/africa/18iht-kafka.1.15381157.html

Davidson, N. (2009). Walter Benjamin and the classical Marxist tradition, International Socialism, Issue 121, Jan 2 2009 [online]. Last accessed Jan 4 2024: http://isj.org.uk/walter-benjamin-and-the-classical-marxist-tradition/ #:~:text=In fact,the-peak-of,precisely-because-of-his-Marxism.

Demos, C. (2023). The Louvre Museum is raising the cost of its tickets ahead of the 2024 Paris Summer Olympics, Delicious., Dec 18 2023 [online]. Last Accessed Jan 3 2024: https://www.delicious.com.au/travel/travel-news/ article/much-tickets-paris-louvre-museum-cost/wq3o9d71#

Dolan, E. (2023), New psychology research reveals why people prefer human-created artwork to AI-created artwork, PsyPost, 3 Aug 2023 [online. Last accessed Jan 8 2024: https://www.psypost.org/2023/08/new-psychology- research-reveals-why-people-prefer-human-created-artwork-to-ai-created-artwork-167429#

Fraser, C. (No Date), Ed Ruscha Value: Top Prices Paid at Auction, My Art Broker [online]. Last accessed 2 Jan 2024: https://www.myartbroker.com/artist-ed-ruscha/record-prices/ed-ruscha-record-prices

Hood, B., Bloom, P. (2006), Children prefer certain individuals over perfect duplicates, Bristol Cognitive Development Centre, Department of Experimental Psychology, Bristol; Department of Psychology, Yale University, Connecticut. Accessed from Science Direct [online]. Last accessed 3 Jan 2024: https://minddevlab.yale.edu/ sites/default/files/files/Children prefer certain individuals over perfect duplicates.pdf

Horvath, P. (2020), The Art of Tax Evasion, The St. Andrews Economist, 27 Nov 2020 [online]. Last accessed 4 Jan 2024: https://standrewseconomist.com/2020/11/27/the-art-of-tax-evasion/comment-page-1/#comments

Hudson, M. (2019). The art world’s great ‘Banana’ moment won’t change a thing, The Independent, 13 Dec 2019 [online]. Last accessed Jan 6th 2024: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/banana- duct-tape-artwork-maurizio-cattelan-artist-banksy-shredded-painting-a9244311.html

Idao, S. (2021), Shakespeare’s Globe uncovers long-lost Shakespeare play, Shakespeare’s Globe, 1 April 2021 [online]. Last accessed 28 Dec 2023: https://www.shakespearesglobe.com/discover/blogs-and-features/2021/04/01/ shakespeares-globe-uncovers-long-lost-shakespeare-play/

Prints and Photographs Division, Photographic Panorama of the Plateau of Sebastopol, Washington, D.C., Library of Congress [online]. Last accessed 7 Jan 2024: https://www.loc.gov/collections/fenton-crimean-war- photographs/articles-and-essays/photographic-panorama-of-the-plateau-of-sebastopol/

Proust, M. (1913) À la recherche du temps perdu [In Search of Lost Time], Davis, L. (tran.), Paris: Grasset and Gallimard, London: Penguin Group.

Schaffer, A. (1928). Théophile Gautier and “L’Art Pour L’Art.” [Théophile Gautier and “Art for Art’s Sake”]. The Sewanee Review, 36(4), 405–417 [online]. Last accessed Jan 6th 2023: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27534322.

Squiers, A. (2021). Bertolt Brecht in Context, Part II: Brecht’s Work, Chapter 14: Brecht and Marxism, 28 Mary 2021, Cambridge University Press [online]. Last accessed Jan 4th 2024: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/ bertolt-brecht-in-context/brecht-and-marxism/3B52C4B61A4B6A2C964C68BAB9A283E3.

Wilcox, J. (1953). The Beginnings of l’Art Pour l’Art, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 11.4, pp. 360–77.

Woodis, W. (No Date), Fenton Crimean War Photographs, Washington D.C., Library of Congress, [online]. Last accessed 8 Jan 2024: https://www.loc.gov/collections/fenton-crimean-war-photographs/about-this-collection/#